THEORETICAL OBSERVATORY

Aporias (Apparent Contradictions), 1987

Methodological notes on the reversal of perception

When we encounter a work that represents recognizable objects — fabrics, geometric volumes, metallic surfaces — our brain automatically activates a recognition process. “I know this form,” we think. “I know what this is.” And yet, something doesn’t add up. The initial certainty falters, and we find ourselves in a state of cognitive suspension: we see clearly what is represented, but we are unable to grasp its overall meaning. This phenomenon, which could be described as a perceptual short circuit, arises from a fundamental contradiction: the work presents us with elements drawn from the real world, yet arranges them according to logics that contradict our everyday experience. The result is neither informal, where representation is wholly abandoned, nor traditional realism, where the world is reproduced according to its physical laws. It is something else altogether.

The research on the reversal of reality began in the second half of the 1980s with a series of paintings, three‑dimensional objects, and photographs. Alongside the “visual psychic archetypes” and the “defunctionalizations,” this body of work emerged through an engagement with neuroscience, particularly the studies of John C. Lilly on consciousness and perception. His experiments in sensory deprivation tanks — environments that isolate the subject completely from external stimuli — allowed direct observation of the mechanisms through which the brain constructs reality in the absence of habitual sensory input. These experiences revealed that perception is not a passive recording of the external world, but a constructive activity of the mind that organizes stimuli according to learned patterns. From this neuroscientific understanding arises the possibility of an artistic practice that intervenes precisely in these mechanisms of perceptual construction. Unlike the defunctionalizations, which strip objects of their function, here the function is inverted, contradicted, overturned. The work operates on an ontological level: what is an object when freed from what it is supposed to be? When we look at an object, the brain compares what it sees to stored images and returns a name. This process feels natural, but it is in fact a learned cultural mechanism. The work acts upon this process: it takes common elements — industrial materials, objects, fabrics, woods, porcelains — fragments and recomposes them according to rules that contradict our expectations. Identifying the original materials is irrelevant: what matters is the perceptual suspension that arises when we can no longer name what we see. This is not about displacing finished objects, as in decontextualizations. Instead, components are assembled according to a logic that is consistent yet contrary to conventions of use. Each work is a closed system, a new object. It is not a ready‑made: it is a constructive project that generates visual forms endowed with strong aesthetic autonomy. By forcing materials out of their functional roles, configurations emerge that belong neither to design nor to traditional sculpture, but to a hybrid territory where formal value coincides with perceptual experimentation. The result? We may recognize individual parts, yet fail to name the whole. When a metal cylinder is reassembled according to a logic that denies its intended function, an aporia is produced: a deadlock in thought that forces us to pause in uncertainty rather than settling on a reassuring definition. For instance, a piece of fabric used as a base for a heavy iron plate. Or transparent glass placed to conceal something. Fabric normally covers; it does not support. Glass allows us to see through; it does not hide. Each material retains its physical properties but loses its socially assigned role. The objects continue to exist physically, yet the brain can no longer classify them. The work appears at once completed and unstable, functional and useless, familiar and alien. These opposing pairs coexist, generating an unresolved tension — and that is precisely the point: the tension must be experienced. By accepting contradiction, we come to see that the categories through which we organize experience are arbitrary social constructions, not natural laws. Why must fabric cover and not construct? Why must metal support and not decorate? Faced with such works, the mind seeks answers that are continuously denied. This failure produces a precise effect: the object ceases to be transparent to consciousness. In everyday life, the objects we use are transparent — a chair is simply “something to sit on,” and its materiality disappears behind its function. Here, the opposite occurs: the function disappears and only the reorganized materiality remains. The object regains its concrete presence — form, weight, color, surface. It returns to being a thing before being an instrument. Uselessness becomes a strategy. A useful object defines our field of action, it conditions us. A useless object leaves us free — though it is an uneasy freedom, one that demands we decide what it means. Uselessness suspends the social destination of the object, allowing us to observe it as a pure organization of matter in space. Our everyday experience of objects is entirely mediated by use. A hammer is “what I use to drive nails,” a cup is “what I drink coffee from.” Identity coincides with function. But ontologically, this coincidence is a cultural illusion. The object exists independently of its function: it has mass, space, temperature, composition — physical properties that exist irrespective of human use. These works operate on the fracture between being and function. Objects are forced to reveal their pure ontological dimension: they continue to exist even when no longer serving any purpose. By losing their social function, they become more visible as autonomous material entities. Each work is a perceptual experiment. Its results should be observed as data, emerging when material reality is dismantled and reassembled according to rules that differ from socially shared ones.

In conclusion, these apparently absurd configurations demonstrate that everyday reality is only one among infinite possible organizations of matter. What we call “normality” is simply the version selected by our culture. These assemblages do not create imaginary worlds; rather, they reveal that the world we inhabit is an arbitrary, historical, and modifiable choice. The strength of this approach lies in its anticipatory nature: long before today’s discourse on multiple realities, augmented worlds, post-truth, and simulation, this work already showed — through physical objects — that the perception of reality is never neutral, but always constructed.

V R

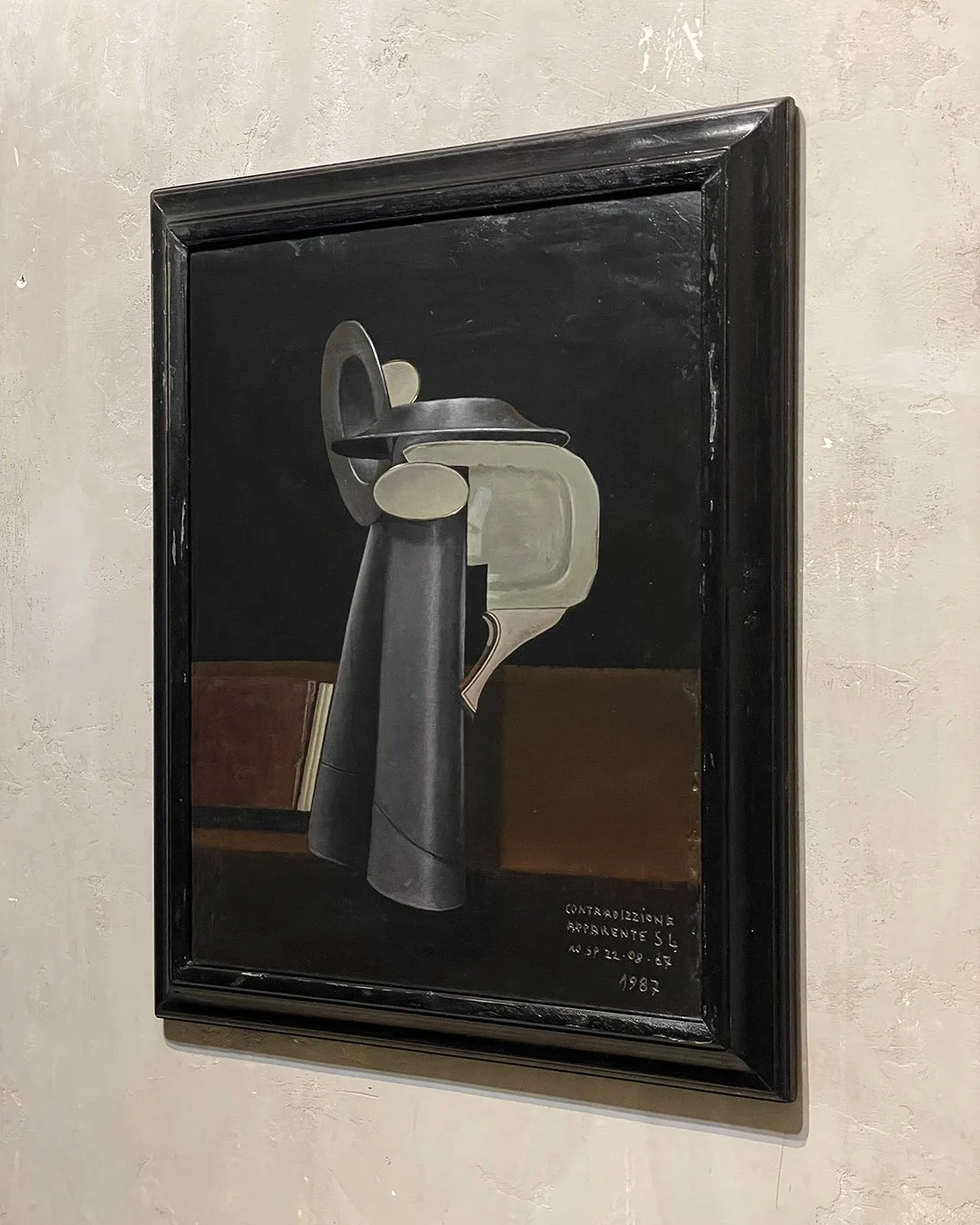

Apparent Contradiction S4. 1987©. 50x40 cm, tempera on wood.

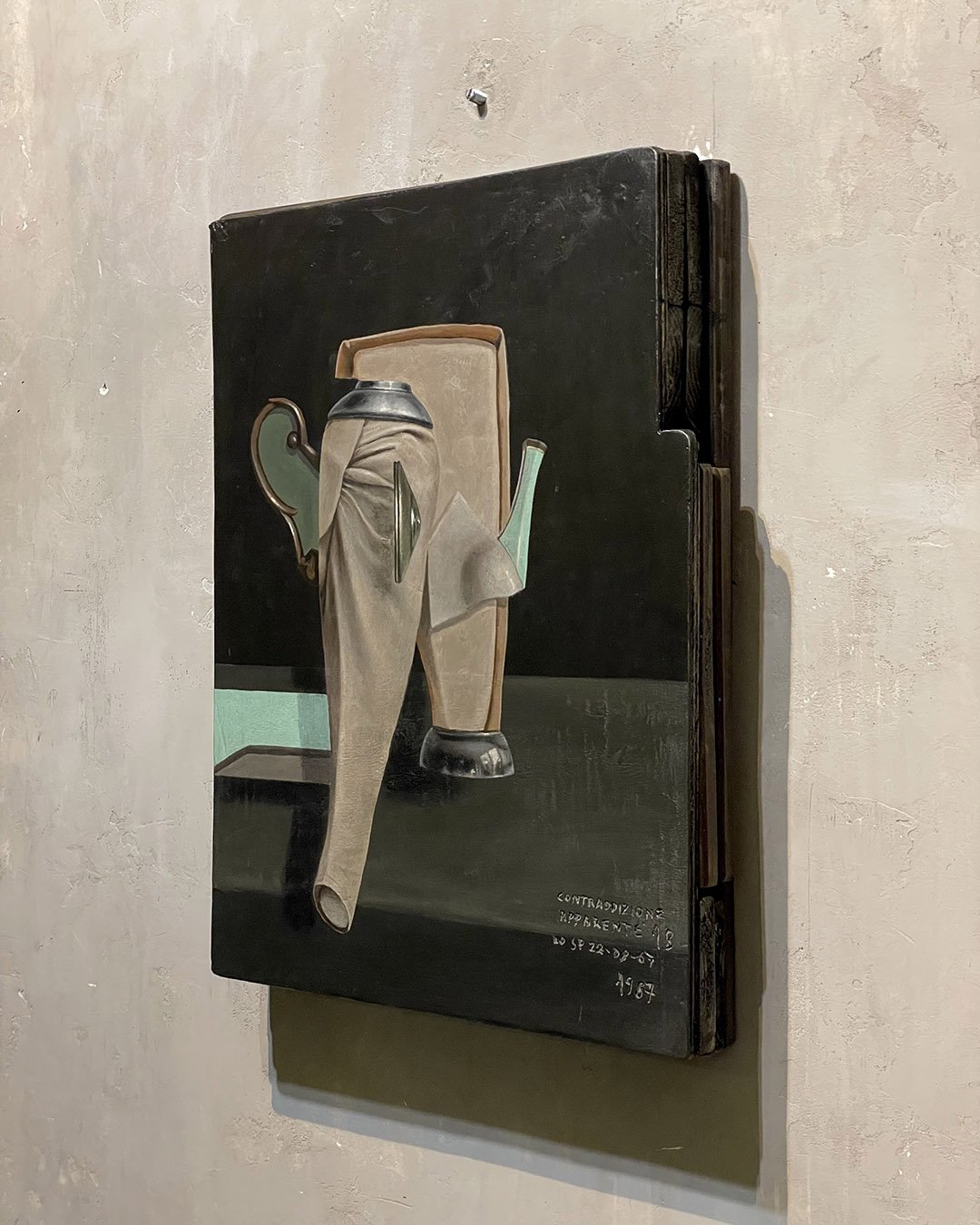

Apparent Contradiction 1b. 1987©. 50x40 cm, tempera on wood.

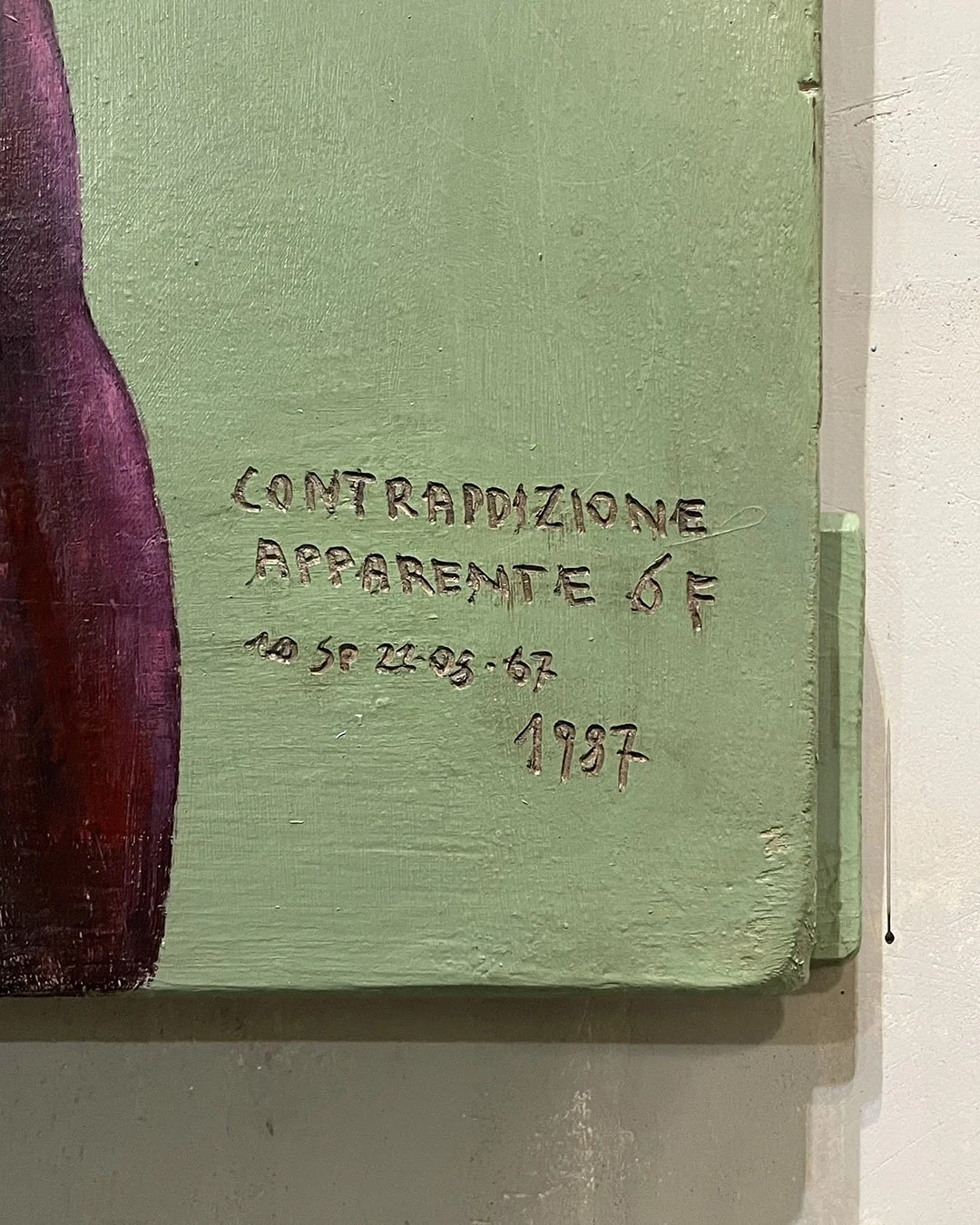

Apparent Contradiction 6F. 1987©. Tempera on wood, 83x56 cm.

Apparent contradiction M1. 1988©. Cm 84x50, tempera on wood.

Apparent contradiction 2f. 1987©. Cm 40x30, tempera on wood.

Apparent contradiction 4L. 1987©. Cm 40x30, tempera on wood.

Privacy Policy Image Licensing

All rights reserved Virgilio Rospigliosi 2023© Design by Lux Aeterna Multimedia